I’ve been teaching Mixing and Mastering as an early project in my advanced Music Tech course for about 6 years, and I’ve found it to be one of the more challenging and rewarding parts of the curriculum. It’s easy to pick an assignment that is either too hard or too simple, and ignore the practical elements of mixing.

Somewhat controversially, I teach mixing using Ableton Live. I do this because I like using this software. Specifically, I feel that track groups are a superior tool for a beginner compared to auxiliary sends. Since Ableton can do both (and most other programs only use aux sends) I prefer using Live.

The process

For this project, I use a “raw” Recording Club project – that is, one with all the multi tracks recorded but no mixing applied to it. To keep the project organized, I have pre-organized the set into Drum, Guitar and Vocal groups.

We start with the Guitars. In our set, the guitars were recorded D.I. style – no amps of any kind were applied. This frees us to pick the guitar sounds using Ableton’s Amp and Cabinet effects. We spend a day learning about what different combinations of amp and cabinet sound like and apply them to our tracks. We also apply high-pass filters to both guitar parts and compress the Guitar track group.

Next, we mix the vocals. Using only the track group (the sub-tracks represent individual takes) we apply a high-pass filter, compression, simple delay (time-based to about 100ms with about 20% dry/wet), reverb, and possibly overdrive/saturator to get a “live” Rock sound.

Then, we mix the drums. Because drums are the trickiest to mix I teach drum replacement for the kick and snare tracks. Using Ableton’s “Convert Drums to new MIDI track” feature we isolate the snare and kick notes and replace those notes with a superior drum sound. We then turn down the cymbal overheads and compress the Drums track group.

After applying a final mix among the three groups, we apply Full Chain Master to the master track to get the track up to standard volume levels. To test the master quickly, we simply play our song at the same time a track from iTunes (at full volume) of the same style is playing. If we can hear both at the same time and with the same basic frequency content, we’re good to go.

Unpacking the process

So, my readers may be in two camps over this project. One camp is frothing at the mouth over my oversimplification of the mixing process. To those, I apologize – I have attempted in the past to further explore the nuance and personal choice a true engineer experiences and it complicates the project too much for the average student trying to keep up.

To mention the point of drum replacement specifically – I do demonstrate how proper recording, mic choice, placement, and room can influence a drum sound. Then I conclude that we do not have the proper environment to achieve this without doing human single-drum overdubs, which are simply not in our league.

Another camp may be wondering how I’m teaching mixing at all, and where I got these multitrack recordings from – simply put, it took a lot of time to collect material that works for this project. I’ve tried songs from classes I have taken as well as ones I have helped record and mix, and right now the track included in this post is doing the trick. This is the only project I do where the students all work on the same exact song, and it amazes me how differently the tracks can turn out.

How it turns out

Here’s how the track sounds when they start:

Here’s the example that I mixed along with the students – not perfect, but I don’t think it sounds too shabby. Loud drums, live vocals, and nice sounding guitars:

And now for a couple students’ versions – first, one with the very common issue of the voice sitting too loudly in the mix:

And another common problem, the voice sitting to soft in the mix:

This one sounded like a fairly good mix, although the voice could use a little bit more effect – compared to the rest of the track it sounds raw. I love the Dick Dale-style guitar delay. Overall pretty good though:

And finally, what happens when drum replacement goes wrong. Basically what you’re hearing is a Drums-to-MIDI track made from an overhead track rather than a spot mic track. Also, the student used the default 808 drum kit sounds, rather than a suitable replacement:

Moving ahead with mixing

Even though my advanced Music Tech class is not all about mixing and recording, doing this project immediately makes students more sensitive to the ideas of balance, mastering and complex effect chains. Of course, before doing this project we have to cover dynamic processors (gate, compressor, etc.) pretty extensively – it would be a lot to introduce those concepts along with the mixing issues.

I have noticed that the earlier I put this project and the more thoroughly we produce these mixes, the better subsequent projects sound. Mixing a typical rock song actually opens students to making more complex and detailed electronic music, and allows them to explore the possibilities of the effect chain and track groups.

Download

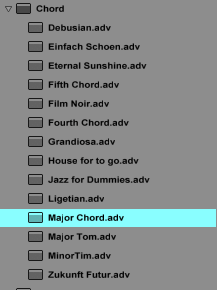

Click here to download the Ableton Packs for the unmixed version and my mixed example version. These use effects that require Ableton Live 9 Suite edition.

Unmixed version

Mixed version